Introduction

The most common cause given for the Great Depression was the stock market crash of October 1929. On October 23 to November 13, the Dow Jones Industrial Average dropped almost 40 percent, from 327 to 199. Stocks rebounded, as historian Maury Klein has noted, by March 1930, the Dow had recovered 74 percent from their December level. Stocks later fell, but that was a consequence of the Depression, not the cause.

In his article in Forbes magazine, Larry Fleisher argues, "The idea that capitalism caused the Great Depression was widely held among intellectuals and the general public for many decades." None of these familiar scapegoats solve the puzzle. Events like The Stock Market Crash of 1929, The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, and President Herbert Hoover cannot shoulder the blame. Why did the economy continue getting worse? Between 1933 and 1934, the unemployment rate was one in four people.

Keynes on Deck

In 1936, English economist and philosopher John Maynard Keynes provided his answer in The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. A simple Keynesian model states that government spending adds to total demand, adding more to production and hiring more workers. The breakdown here is an insufficient "effective demand"- what economists now call "aggregate demand." [3] People and firms weren't spending enough. In response to Keynesian critics who believe that markets can remain broken, Austrians point to the U.S. depression of 1920-1921 as an example of a market-based recovery. [7] According to Keynes, this self-reinforcing dynamic occurred to an extreme degree during the Depression, when bankruptcies were common and investment, which requires a degree of optimism, was very unlikely to occur. Economists often characterize this view as opposing Say's Law, where production is the key to economic growth and prosperity, and that government policy should encourage (but not control) production rather than consumption.

What was the Cure?

The American government under Herbert Hoover remained true to the idea of a laissez-faire economy, or no government involvement in the economy. Despite rising unemployment, President Hoover refused to get the government involved. Hoover cut taxes, created a federal agency to buy excess farm crops, and increased federal spending on public projects like Hoover Dam. Hoover also established the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, which gave emergency loans to banks and businesses hoping to increase business. Over 100,000 businesses had failed by this time, and 25% of the population was out of work.

By 1932, the American public had lost faith in Pres. Hoover and the 1932 presidential election saw Franklin Roosevelt (FDR) win in a landslide. FDR introduced The New Deal, a series of financial reforms, public work projects, regulations, and other programs, between 1933 and 1938 to counter the effects of the Great Depression. The New Deal consisted of safeguards, constraints on the financial industry, and efforts to re-inflate the economy after prices had fallen sharply. In her article "Ending of the Great Depression," Christina Romer argues that her findings dispute studies that suggest that the recovery from the Great Depression was due to the self-corrective powers of the U.S.

Murray Weidenbaum notes that during the New Deal, the Federal Government began to use its procurement policies to promote economic and auxiliary social objectives, continuing these policies into World War II; this practice has outlived by decades the emergency conditions that initially prompted it.

America, "The Arsenal of Democracy"

In the 1930s, Congress passed several bills that prevented the United States from supplying war materials to combatants. FDR started preparations for war before the Pearl Harbor attack in December 1941. (The Cash and Carry Policy of 1939) and refused to provide loans to any nation that had defaulted on its debts from World War I. The Lend-Lease Bill of March 1941 passed Congress quickly. He was signed by FDR, which authorized FDR to sell, trade, lease, or military hardware. By the time the war ended, the Lend-Lease program had sent between $40 and $50 billion worth of military aid to Allied countries.

Military Keynesianism is an economic policy based on the position that the government should raise military spending to boost economic growth. It is a fiscal stimulus policy as advocated by John Maynard Keynes. However, where Keynes advocated increasing public expenditure on socially beneficial items (infrastructure), additional public spending is allocated to the arms industry.

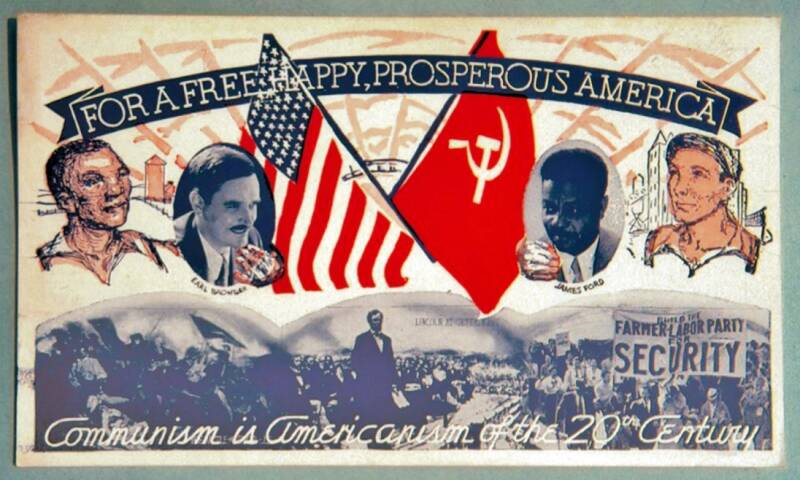

A Marxist POV

Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises was one of the leading critics of state socialism. Socialism, Mises theorized that a highly socialized economy would be ineffective, as its planners could not undertake economic calculation, lacking the prices provided by the marketplace.

In the General Theory, Keynes later responded to the socialists who argued, especially during the Great Depression of the 1930s, that capitalism caused war. He proposed that if capitalism were managed domestically and internationally, it could promote peace rather than conflict between countries. His plans during World War II for post-war international economic institutions and policies, which contributed to the creation of the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, and eventually the World Trade Organization, were aimed to give effect to this vision.

Historiographical Adjustments

Austrian economist Josef Steindl provided the most sophisticated version of the economic maturity idea. Not surprisingly, he did so in part by explicitly situating the Great Depression in the United States within a long-term development framework. His work linked economic stagnation directly with the behavior of capitalist enterprise, thereby avoiding the mechanical qualities of many of the stagnation arguments and their frequent appeals to external factors. Steindl's version of the maturity thesis was that long-run tendencies toward capital concentration, inherent in capitalist development over time, led to a lethargic attitude toward competition and investment.

Steindl's thesis carries significant implications for our understanding of economic stagnation. As he presents it, the concept of long-term alterations in industrial structure suggests that the economy as a whole becomes less capable of recovering from cyclical instability and generating continued growth.

Conclusion

There is no general agreement about its causes, although there tends to be some consensus regarding its consequences. Those who at the time argued that the depression was symptomatic of a profound weakness in the mechanisms of capitalism were only briefly heard. The New Deal started to help end the Great Depression. To accelerate the process, it would take more than just this spending to end the Great Depression. The solution came in the rapid acceleration in manufacturing found in war.

References:

Bernstein, Michael A. “The Great Depression as Historical Problem.” OAH Magazine of History 16, no. 1 (2001): 3–10. (p.7,8) Accessed Sep 16, 2024. URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25163480.

Corey, Lewis. The Decline of American Capitalism. New York: Covici Friede Publishers. 1934. URL: https://www.marxists.org/archive/corey/1934/decline/index.html.

de Rugy, V. Military Keynesians. Reason, 44, (12, 2012). p.19-20. URL: https://www.proquest.com/magazines/military-keynesians/docview/1140419184/se-2.

Fleisher, Larry. "The Great Depression and The Great Recession." Forbes. Marx/Engels Internet Archive. 2009. URL: https://www.forbes.com/2009/10/29/depression-recession-gdp-imf-milton-friedman-opinions-columnists-bruce-bartlett.html.

Foldvary, Fred E. “The Austrian Theory of the Business Cycle.” The American Journal of Economics and Sociology 74, no. 2 (2015): 278–97. URL : http://www.jstor.org/stable/43818666.

Higgs, Robert. "Crisis, Bigger Government, and Ideological Change: Two Hypotheses on the Ratchet Phenomenon." Explorations in Economic History 22, no. 1 (1985): 1, URL: https://go.openathens.net/redirector/liberty.edu?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/crisis-bigger-government-ideological-change-two/docview/1305246411/se-2.

Keynes, John Maynard. The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1936.

Markwell, Don. John Maynard Keynes and International Relations: Economic Paths to War and Peace. Oxford: New York, 2006.

Marx, Karl. "Capital. A Critique of Political Economy, Volume I." Marx/Engels Internet Archive. 1995, 1999. URL: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/index.htm.

Romer, Christina D. “What Ended the Great Depression?” The Journal of Economic History 52, no. 4 (1992): 757–84. URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2123226.

Samuelson, Robert J. “Revisiting the Great Depression.” The Wilson Quarterly (1976-) 36, no. 1 (2012): 36–43. URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41484425.

Schweikart, Larry. The Economic Impact of War on Business. Liberty University. URL: https://canvas.liberty.edu/courses/685821/modules/items/74960635.

"Series Y 904-916: Military Personnel on Active Duty: 1789 to 1970." Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1970, Part 2 (Bicentennial Edition).

United States Census Bureau. September 1975.p.1135.

Von Mises, Ludwig. Socialism: An Economic and Sociological Analysis. Sixth edition. Indianapolis: Liberty Classics, 1981.

Add comment

Comments