In just over ten years, the aeroplane became an effective killing machine.

The thrill of aviation has held mankind's imagination since he first watched the birds in the sky. The early 20th century was a pivotal moment in history, with the addition of submarines, tanks, long-range artillery, and aircraft. Since 1903, man has proven that powered, controlled flight is possible above the dunes of North Carolina. The Great War of 1914-1918, or the First World War, was a critical period in which both sides tested new technologies and transitioned out the old. A mere ten years later, the world's armed forces began to examine various applications the aircraft offered. First World War airpower is often viewed as insignificant concerning the broader conflict. These conceptions oversimplify the impact of pursuit and bomber aviation and ignore the role of aerial observation and overall battlefield integration. The use of early aviation in ground support roles significantly contributed to the war on the ground. While limited by technology and doctrine, the lessons of early aviation learned during that period directly influenced the development of more effective air-ground coordination in later conflicts. Over a century ago, mankind incorporated the aeroplane into its killing machine inventory. The research will examine the opposing sides and their approaches to aerial close support.

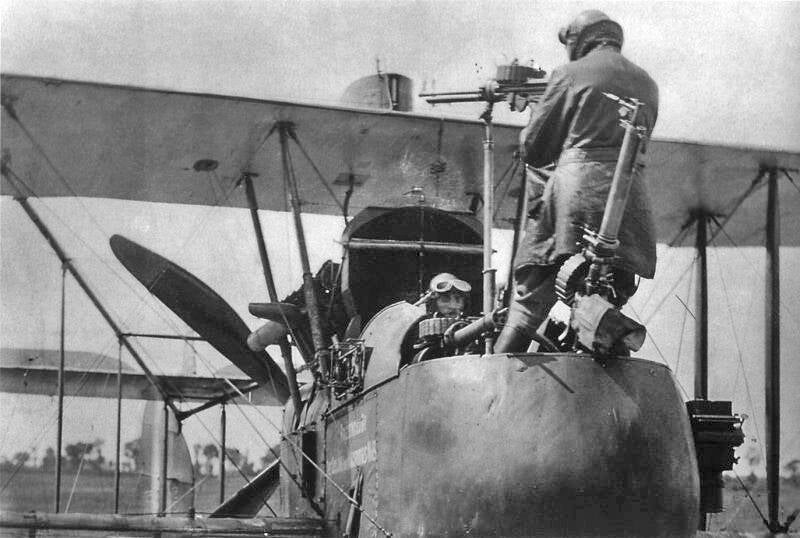

A crewman demonstrating how the camera works on a RFC B.E.2c, 1916.

IWM Q33850 Imperial War Museum, Public Domain.

Fokker E.1 Eindekker in 1915/early 1916.

From the Peter M. Grosz collection, Public Domain.

The Deutsche Luftstreitkräfte (Imperial German Air Service) pioneered recognizing aircraft's potential beyond reconnaissance. Many of Germany's records were lost or destroyed, but the Bavarian records are mostly intact. Researching this project pulls together data for the former Allied and Central Powers combatants and produces a fuller picture of the events. Data and narratives from 1914 and beyond will be influenced by the victors and the vanquished. Bringing together the verifiable facts from both sides of the conflict should give a more complete narrative than relying on the records of those who won. There is always more than one side of a story. The main approach to the subject is chronological, starting with the simple aircraft of 1914 and progressing to the combined arms used in 1918.

Do you know why this subject? We did not pick up the GAU-8 30mm cannon tank-buster; there is a long evolution from simple, underpowered biplanes to the A-10C Warthog. Imagine the early days of aerial warfare, beginning with pistols and rifles firing between reconnaissance aircraft over the front lines. As the war progressed, Germany developed a more structured and tactical approach to air combat and ground support: The Luftstreitkräfte organized specialized ground strike aircraft, Schlachtflieger (Battle Flyers), in dedicated Schlachtstaffeln (Battle Squadrons).[1] Jagdstaffel (Fighter Squadron) escorted these ground strike aircraft, which consisted of fast and maneuverable fighters offering top cover. The Luftstreitkräfte's integration of ground attack and fighter escort tactics laid the foundation for modern combined arms operations. The German approach demonstrated that air power could be used to observe or defend and actively shape the battlefield.

Is this a characteristic of a military culture? Conversely, the British Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and France's Aéronautique Militaire (Military Aeronautics) initially focused on reconnaissance and air superiority, much like their German counterparts. The Allies chose to modify existing aircraft that were made obsolete by newer German aircraft and were not really 'ground attack aircraft' but 'aircraft used for ground attack. It would not be until 1918 that the Allies would develop mission-specific aircraft to support the troops on the frontline and strike behind the lines into German supply depots and troop concentrations. While the Germans were early adopters of specialized ground attack tactics, the Allies evolved their approach more gradually—initially through improvisation, and later through innovation. By the end of the war, both sides had demonstrated the strategic value of air power in direct support of ground operations, setting the stage for its expanded role in future conflicts. Ground support aviation between 1914 and the Battle of France in 1917 evolved significantly as military doctrines adapted to the realities of trench warfare and technological innovation. At the onset of war, Unarmed or lightly armed aircraft like Britain's Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2 and France's Voisin III aircraft served in a support role, spotting artillery shots and conducting photographic reconnaissance.[2] With no formal aerial ground attack doctrine, aircraft were vulnerable to attack from enemy fighters like the French Morane-Saulnier Type N Bullet and German Fokker E1 Eindekker. The introduction of synchronized machine guns, firing through the propeller arc without striking it, was a game-changer, and the shoot-downs began to multiply. Britain and France used outdated aircraft, like the Sopwith Camel, and reconnaissance aircraft were retrofitted with light bombs and machine guns.[3] British Airco DH.4 and France's Breguet 14 made low-level strikes as the war progressed, disrupting troop concentrations and bombing supply depots. German Schlachtstaffeln of Halberstadt CL.II's and Hannover CL. III's provided tactical ground support, coordinating with infantry and other ground units.[4] During the second half of 1917, the Deutsche Luftstreitkräfte fielded the world's first metal ground support aircraft, the Junkers J.1.An armor-plated engine, fuel tank, and cockpit gave the aircrew a measure of protection from ground fire.

German Halberstadt C.V. SDASM Archives, Public Domain.

Outclassed by new German fighters, the F.E. 2d was used for close air support in 1917. (The observer is demonstrating the use of the rear-firing Lewis gun). IWM Q69650 Imperial War Museum, Public Domain.

By 1918, the Allies had learned from earlier setbacks and began to coordinate air and ground forces more effectively. The American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) began offensive operations, adding a third air force to help rejuvenate the British and French efforts. American-equipped squadrons of Breguet 14's and De Havilland DH. 4's with American-made Liberty engines joined the Allied offense by strafing trenches, bombing artillery positions, and disrupting enemy logistics.[5] Using radio, signal panels, and signal flags allowed ground troops to communicate with aircraft, which applied machine gun fire and light bombs where needed. On August 26, 1918, American air forces and the Allies achieved air superiority over St. Michel, which permitted ground attack aircraft to operate with impunity.[6] These coordinated efforts weakened German defenses, disrupted reinforcements, and boosted the effectiveness of infantry assaults. Consequently, on September 29, 1918, in the Argonne Forest, the support aircraft of the Deutsche Luftstreitkräfte counterattacked and permitted the ground troops to hold the line, blunting the American advance. During the Hundred Days Offensive (August–November 1918), combined arms tactics helped cause a collapse of the German Hindenburg Line.[7] Towards the end of 1918, it was clear that Germany could no longer mount a successful defense. Unable to continue, Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicated, and the newly proclaimed Republic of Germany surrendered. The Great War was over after four years of killing the better part of a generation. With the signing of the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, Germany's military air arms during World War I, the Luftstreitkräfte of the Imperial Army and the Marine-Fliegerabteilung of the Imperial Navy, were disbanded in May 1920, effectively banning Germany from having any air force. The "War to End All Wars" mentality let air power lessons slip away, and the doctrine and tactics of close air support were shelved. The true impact of airpower during the war is shown through combined arms operations rather than viewing aircraft, submarines, or any of the new weapons systems as a singular weapon.

The calm before the storm. An RFC Chaplain conducts a Sunday service using an F.E.2c as a makeshift pulpit. "Bidden or not bidden, God is present."

IWM Q12109 Imperial War Museums, public domain.

Barker, Ralph, The Royal Flying Corps. London: Constable and Company. 1995.

Duiven, Rick and Dan-San Abbott. Schlachtflieger! Germany and the Origins of Air/Ground Support 1916-1918. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Military Press, 2006.

Hart, Peter. Somme Success: The Royal Flying Corps and the Battle of The Somme 1916. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Books, 2012.

Hallion, Richard. P. Strike from the Sky: The History of Battlefield Air Attack, 1911–1945. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1989.

Hudson, James J. Hostile Skies: A Combat History of the American Air Service in World War I. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1968.

Johnson, Herbert A. Wingless Eagle: U. S. Army Aviation Through World War 1. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

Treadwell, Terry C. Strike from the Air. Havertown: Pen and Sword Books, Ltd. 2020.

Add comment

Comments