A common challenge to mankind has been preserving food to be available during foul weather and low food supplies. For centuries, most foods were only available at certain times of the year, known as seasonality. At the beginning of the twentieth century, American naturalist Clarence Birdseye was working in Newfoundland and learning from a local Inuit how to ice fish that, when thawed, still tasted fresh. This discovery would be the beginning of the innovation of freezing and preserving process of various foods for later consumption. One of the treasures of America is that its citizens are free to explore and innovate. The free market economy, with its potential to reward the inventor who creates a product, tool, or process to achieve a marketable goal, is critical in promoting such innovations to consumers.

Born on December 9, 1886, Clarence Birdseye spent his early years in Brooklyn, New York. As a child, Birdseye's interest in natural science taught himself by correspondence taxidermy. This interest in nature matured past high school to his degree work in biology at Amherst. During the summer, he worked for the U.S. Department of Agriculture. After finances required Birdseye to leave university, he found himself in Muddy Bay, Labrador, in the Dominion of Newfoundland, where he had a ranch for raising foxes and collecting pelts for sale. During this time, Birdseye was taught the local First Nation Inuit skill of ice fishing under very thick ice. In -40 °C weather, the rudimentary quick-freeze methods of the Inuit demonstrated that freshly caught fish could be then instantly flash frozen when exposed to air and, when thawed, still tasted fresh in the extreme cold of midwinter.

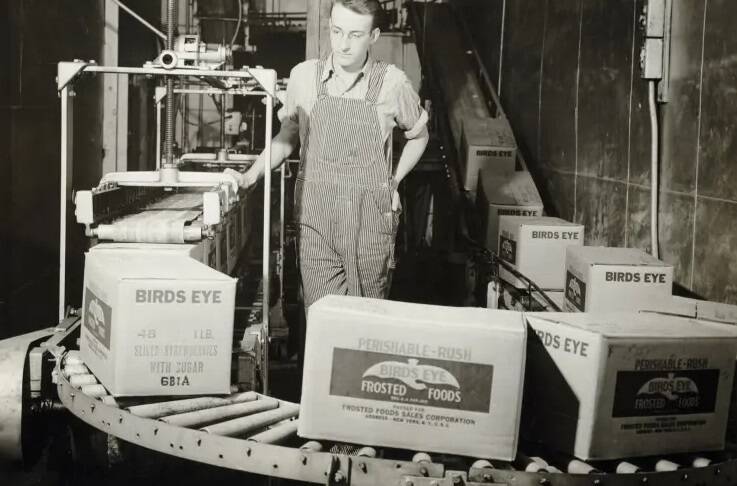

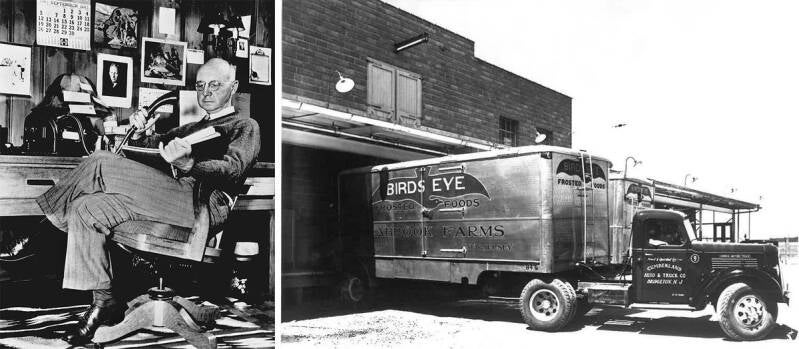

During World War 1, Birdseye took a job as assistant to the president of the U.S. Fisheries Association. Birdseye was still examining what he wanted to do; he did not think of himself as an inventor. But Birdseye's inquisitive nature grew as he became further interested in food preservation, to get it from the source to the consumer by expanding the concept of fast freezing. Birdseye did not just invent an industrial method of copying the Inuit's way of fast-freezing fish; Birdseye looked to couple them with scientific theories and adapt them to quantity production. In Birdseye's case, he recognized the potential market and need for well-preserved frozen food. Birdseye envisioned a package of freezing, packaging, transport, and presentation to the retailer. He scraped together funds to start a frozen fish company and implemented his ideas. Birdseye initially performed home experiments to produce quick-frozen food in consumer packages. After one failed attempt to scale up the process with an under-financed company, he obtained satisfactory financing and formed the General Seafoods Company. Birdseye set up shop in Gloucester, Mass., with a few employees to develop a commercially practical freezer for packaged, quick-frozen foods. He understood that success depends on innovation, which doesn't mean just invention. Birdseye also invented much of the machinery that made mass marketing of frozen products feasible. In 1926, this work culminated in the Birdseye freezer apparatus. The freezer was made in single- and double-belt models. The technology for freezing vegetables was developed in the 1920s by the Birdseye - hence the household name. He leased refrigerated boxcars to distribute frozen foods and was instrumental in developing the freezer display cases that consumers see in grocery stores. A resourceful character, Birdseye also invented dehydrated food and infrared heat lamps for the food industry. A few years of success caught the attention of General Foods, and Birdseye sold out for $23.5 million on July 27, 1929.

Wisdom and the ability to build a successful life come in many forms. This research examined an American who was a lifelong naturalist who became an inventor and an entrepreneur and sold his patented inventions and processes. A wise entrepreneur knows when they have reached the limit of their business skills and can permit their young business to grow further in the business world. History contains examples of businesses where entrepreneurs cannot let go, and the company eventually fails. Birdseye was an original thinker and investigator with enormous curiosity and astute powers of observation. Over his lifetime, he was granted 300 American and foreign patents.

By contrast, the life and works of Albert Thayer Manhan, USN, widely regarded as a brilliant naval theorist, were on a world strategic and tactical level, and his ideas encouraged industrialists and politicians. At the end of his days, the United States was a world power, and its Navy was a global force.

So, where do these two American innovators intersect? In this week's video, “Big Think: Don't Mistake Leadership for Management,” Marc Cenedella, discusses the difference between leadership, a prime characteristic of entrepreneurs, and management, the point where a new business (entrepreneurship) can transition and grow into a company that is managed by professionals who possess the needed skills to facilitate expansion. Birdseye’s interests were as a hands-on inventor, and he could move on when his goals were met. Mahan’s analytical skills examined the past, saw the present, and looked into the future. The industrialists and politicians then carried forward Mahan’s production of books and papers for implementation. The common thread between both men is that they lived in a country where individuals were free to examine and explore their lives. Unlike Europe, where political and social strata were established eons ago, America offers individuals the opportunity to advance on their own merits. This is in keeping with the greatest gift from God, that of choice. As we read from Deuteronomy 30:15-16 (CEV), “Today I am giving you a choice. You can choose life and success or death and disaster. I am commanding you to be loyal to the Lord, to live the way he has told you, and to obey his laws and teachings. You are about to cross the Jordan River and take the land that he is giving you. If you obey him, you will live and become successful and powerful.”

Bibliography

Bennett, Chris. "Clarence Birdseye, the king of frozen food." Western Farm Press, October 8, 2012. Gale Business: Insights (accessed September 9, 2024). URL: https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A304775153/GBIB?u=vic_liberty&sid=summon&xid=693e19c2.

“Big Think: Don't Mistake Leadership for Management.” Liberty University, Accessed: Sep 9, 2024. URL: https://canvas.liberty.edu/courses/685821/modules/items/74960558.

Birdseye, Clarence. Bin for Storage of Fish. U.S. Patent No. 1,805,354. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. (12 May 1931).

Follette, Gordon. "The Formative Years: Frozen Foods." ASHRAE Journal 46, no. 11 (11, 2004): S35, S37,S40-S41, URL: https://go.openathens.net/redirector/liberty.edu?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/formative-years-frozen-foods/docview/220462556/se-2.

Hollett, Matthew. "Clarence Birdseye Eats His Way Through Labrador". Newfoundland Quarterly. (June 2017) Retrieved 8 July 2021. Accessed Sep 9, 2024.

Kelly, Mike. "Clarence Birdseye In Labrador." The Consecrated Eminence: Blog of The Archives & Special Collections at Amherst College. (2013) Retrieved 19 January 2017. Accessed Sep 9, 2024.

Kurlansky, Mark. Birdseye: The Adventures of a Curious Man. Vol. 1st ed. New York: Anchor, 2012. URL: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=741862&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

“The Technology for Freezing Vegetables Was Developed in the 1920s by the American Clarence Birdseye - Hence the Household Name. While Undertaking Biology Research in the Arctic, He Noticed by Chance That Fish Placed on the Ice Immediately after Being Caught Would Quickly Freeze Solid yet Taste Fresh Once Thawed out Later.” Farmers Weekly, no. 1072 (2016).

"Steve, Clarence, Thomas, and Topsy." The OECD Observer no. 286 (2011): 31.

“The Story of Birds Eye begins with our founder, Clarence Birdseye." Retrieved 26 July 2021.Accessed Sep 9, 2024. URL: https://www.birdseye.com/our-roots.

Add comment

Comments