The rebuilding of the economy of a nation after a civil war is a major undertaking. Beginning with a simplified examination of the economic growth between the North and the South and concluding with an examination of business cycle severity of economic fluctuations provided by U.S. economic historian Robert Gallman.

In the post-civil war era after 1865, the overall picture of the former Confederate states was bleak. The economic and social structure was gone forever. Vast stretches of the South lay in ruins. The financial industry faced the loss of capital, and local land prices plunged, resulting in banks closing en masse. Homeless refugees, both black and white, needed food, shelter, and work. The development of Sharecropping gave landowners the agricultural labor needed to replace slaves. In addition, children were introduced into the labor force.

The economics of the cotton industry focused on the bottom line for each production level of cotton and cotton-based products. Through industrialization, textile mills would increase the processing efficiency of cotton, resulting in new mill towns. The Southern states saw a growth of these new mill towns while Northern states saw a decrease in textile mills in this transitioning postbellum economy. The transition of cotton mill production dominance from the North to the South in the postbellum United States can be attributed to a change in the labor force dynamics. By 1880, cotton production was back to 1860 levels, continuing to set new records.[1] By 1900, although the South slowly recovered from the Civil War, it had a more balanced economy. It no longer depended on "King Cotton," but agriculture dominated the southern economy regarding employment and contributions to regional gross domestic product (GDP) well into the 20th century.[2]

Subject One: Economic Growth in the Postbellum North and South

Much of the data for this analysis comes from a working paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) titled "America's First Great Moderation." The paper provides detailed statistics on industrial production growth rates for different periods in U.S. history, including the postbellum era. The examination of economic growth during the postbellum era uncovers trends when comparing the Northern and Southern regions of the United States. By analyzing academic data sources, it is feasible to analyze precise data to assess and juxtapose the economic development of these two areas.

The study suggests that growth rates in the North were similar in both the antebellum and postbellum periods. This indicates economic resilience and continuity in the Northern states despite the disruptions of the Civil War. This would explain why the growth rate in the Northern states remained relatively stable between the antebellum and postbellum periods. In time, New England and Middle Atlantic regions started losing manufacturing employment shares as the nation expanded westward and the southern shift in consumer goods manufacturing.[3]

For the postbellum period from 1867 to 1914, the Industrial Production Growth was:

Mean growth rate: 4.6%

Standard deviation: 7.5%

Coefficient of variation: 1.63

Overall Economic Volatility: The postbellum period (1867-1914) shows a higher coefficient of variation (1.63) compared to earlier periods. This suggests increased economic volatility in the years following the Civil War, which likely affected both regions but may have had a more pronounced impact on the recovering Southern economy.[4]

These figures represent the aggregate U.S. economy, encompassing Northern and Southern states. There was a shift in agricultural production, with cotton and the expanding tobacco farms remaining primary crops in the South. Still, production continued to move westward to states and territories like Arkansas, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Texas.[5]

Subject Two: Business Cycle Severity of Economic Fluctuations

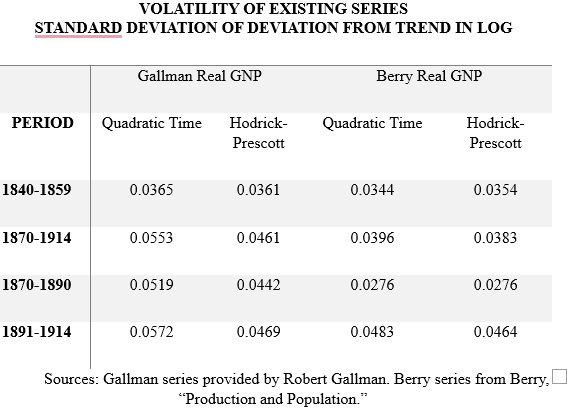

In his series below, nationally recognized authority on U.S. economic history Robert Gallman suggests, "There was a substantial increase in the degree of business cycle severity of economic fluctuations in the United States over the nineteenth century."[1] This can be seen in Table 1, which shows statistics on the Gallman series deviations from two different trends: simple quadratic time trends (time and time squared), separate for each period, and the Hodrick-Prescott trend.[2] In the table below, the set of consistent antebellum-postbellum series is evident in that cyclical movements in industrial production were no larger and were minor in the postbellum period than in the last two decades of the antebellum period. The cyclical volatility of GNP could have been more significant in the postbellum period only because the share of cyclical sectors in aggregate output had grown relative to the share of acyclical agriculture.

The Gallman series appears more volatile over 1870 to 1914 than over 1840 to 1859. Dividing the postbellum period at 1890, the period from 1891 to 1914 appears more volatile than 1870 to 1890, but both appear more volatile than 1840 to 1860. Table 1 also shows statistics for the Berry Real GNP series. The Berry series is only slightly more volatile over 1870 to 1914 than 1840 to 1859 and less volatile over 1870 to 1890 than over 1840 to 1859. Existing output data that cover both the antebellum and postbellum periods are inconsistent and unsuitable for comparing cyclical patterns across the nineteenth century. More consistent data show that output in cyclically sensitive sectors was no less, and probably more, volatile before the War Between the States than after it.

In summation, rebuilding a nation's economy after a civil war is monumental. In time, New England and Middle Atlantic regions started losing manufacturing employment shares as the nation expanded westward and the southern shift in consumer goods manufacturing.

Chandler states in his article, “By the 1880s, the new railroad, telegraph, steamship and cable systems made possible the steady and regularly scheduled flow of goods and information, at unprecedented high volume, through the national and international economies.”[1] America preserved a terrible civil war and emerged as a stronger nation, giving credence to Proverbs 29:18 (Good News Translation), where we read, “A nation without God's guidance is a nation without order. Happy are those who keep God's law!”

Bibliography

Chandler, Alfred D. “Organizational Capabilities and the Economic History of the Industrial Enterprise.” The Journal of Economic Perspectives 6, no. 3 (1992). URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2138304.

Chandler, Alfred Dupont. The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1977.

Calomiris, Charles W., and Christopher Hanes. “Consistent Output Series for the Antebellum and Postbellum Periods: Issues and Preliminary Results.” The Journal of Economic History 54, no. 2 (1994) URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2123921.

Coclanis, Peter A. “More Pricks Than Kicks.” Study the South. University of Mississippi. 2024 URL: https://southernstudies.olemiss.edu/study-the-south/more-pricks-than-kicks/

Davis, Joseph, and Marc D. Weidenmier. “America’s First Great Moderation.” The Journal of Economic History 77, no. 4 (2017) URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26787063.

Davis, Joseph and Marc D. Weidenmier. America’s First Great Moderation, Working Paper 21856. National Bureau of Economic Research. January 2016 Cambridge, MA.

URL: http://www.nber.org/papers/w21856

Flamming, Douglas. Creating the Modern South: Millhands and Managers in Dalton, Georgia, 1884-1984. Univ of North Carolina Press, 2000.

Glaspell, Archie. "Growth in the Postbellum Economy," USS Texas Lives (blog) WordPress. August 30, 2024. URL: growthinthepostbellumeconomy.wordpress.com.

James, John, "Changes in Economic Instability in 19th-Century America," American Economic Review, 83 (Sept. 1993).

Kydland, Finn, and Edward Prescott, "Business Cycles: Real Facts and a Monetary Myth," Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review, 14 (Spring 1990).

Smiley, Gene. “US Economy in the 1920s”. EH.Net Encyclopedia, edited by Robert Whaples. June 29, 2004. URL h\ttps://eh.net/encyclopedia/the-u-s-economy-in-the-1920s/.

Add comment

Comments